Skulls from the Josef Hyrtl Collection at the Mutter Museum, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia (AFP) - For years, a man’s giant intestine was anonymously on display at a US medical museum in Philadelphia, identified only by his initials JW.

Today, the donor display for Joseph Williams depicts not only his anatomical record, but his powerful life story.

After two years of controversy over how to ethically exhibit human remains, the Mutter Museum announced last week it has changed its policy to “contextualize” and de-anonymize its collection.

“The issue isn’t whether we should or shouldn’t exhibit human remains,” said Sara Ray, the museum’s senior director of interpretation and engagement.

“But rather, can we do so in a way that does justice to these individuals and their stories as we trace the history of medicine, bodily diversity, and the tools and therapies developed to treat them?”

Surgical tools through the centuries are stored in special shelves in the stacks at the Mutter Museum, a medical history library in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Founded in 1863 from the personal collection of local surgeon Thomas Mutter, the museum is now home to 35,000 items, including 6,000 biological specimens. Visitors can view a vast medical library with human skulls, wax moldings of skin conditions, medical tools and more.

Under its new policy, the museum will only accept donations from living donors or from their descendants, to help identify them.

In 2020, a heart transplant recipient donated his old enlarged heart to the collection.

The organ, the size of a soccer ball, now floats in a jar next to a collection of 139 human skulls amassed by a 19th century Austrian anatomist.

- Postmortem Project -

Visitors exit a special event at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a medical library that houses more than 37,000 items in its collection ranging from conjoined twins to a collection of 139 skulls and medical instruments

In 2023, after a change of leadership, the Mutter launched the Postmortem Project, a two-year public engagement initiative to re-examine its collection and debate the ethics of displaying human remains.

As part of the reevaluation, the museum deleted hundreds of videos from its YouTube channel, which has over 110,000 followers, as well as a digital exhibition from its website.

“That’s when the controversy started,” recalls the Mutter’s former director Kate Quinn, who initiated the project. “They were internal conversations that became very prominent in the public sphere after the videos were removed from YouTube.”

She added: “We didn’t want to dramatically change the museum. That was never the intent. The intent was to bring people into the conversation and bring us along this journey as we’re trying to figure it out.”

The museum’s annual Halloween party, known as Mischief at the Mutter, was also cancelled.

The backlash was swift.

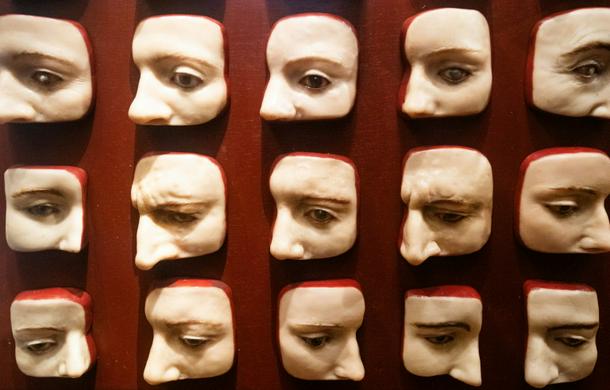

Wax moldings of various eye diseases at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A former director of the museum published a scathing op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, condemning “cancel culture” and accusing “a handful of woke elites” of jeopardizing the museum’s future.

Soon, an activist group called Protect the Mutter, was formed. Its petition calling for Quinn’s ouster garnered more than 35,000 signatures.

“The online content (was) just being decimated, and the staff changes and events,” an organizer at Protect the Mutter told AFP on condition of anonymity.

Upset about the controversy, the heart transplant patient had at one point asked for his heart back before the museum made changes.

- ‘Did these people choose to be there?’ -

Along the corridors of this two-story brick building, visitors can see the cast figures of two adult Siamese twins or study small fragments of Albert Einstein’s brain.

Visitors to the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania examine one of its most famous displays: the wax model of Madame Dimanche, a woman from Paris with a cutaneous growth resembling a horn

They can also learn about the lives of Ashberry, the woman with dwarfism, and Williams, whose “megacolon” was 8 feet (2.4 meters) long. A typical human colon is about 5 feet long.

Similar controversies have also rocked several other Western institutions, such as the British Museum, in recent years, which anthropologist Valerie DeLeon says is part of a broader conversation on ethics.

Museum goers “are thinking about the people that are represented in those collections. And you know, did these people choose to be there? Are they being exploited by having their skeletal remains on display for ‘entertainment’?” DeLeon told AFP.

Quinn left her post this spring and the museum’s new management moved to restore 80 percent of the videos on its YouTube channel, a decision welcomed by members of Protect the Mutter.

But more difficult questions remain, like what to do with the skeleton of a 2.29-meter giant who cannot be identified.

The anonymous Protect the Mutter activist believes it should be displayed.

“Let this example of acromegaly be respectfully displayed and help future generations better understand an ongoing condition that continues to affect people every day,” the activist said.

“It becomes that acknowledgment, instead of erasing the past.”